Works and Process

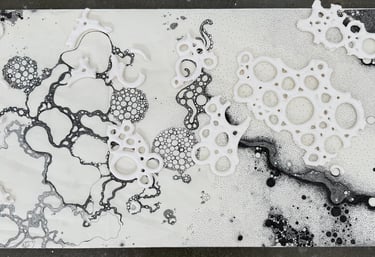

This section brings together the first trials that shaped my language. I started with an interest in translucency and hidden layers and tested how clay, glaze, resin-like skins, and simple prints could register those ideas. The aim was not skill display but to identify what carries the concept with clarity: flow, residue, and the visibility of time.

Material studies

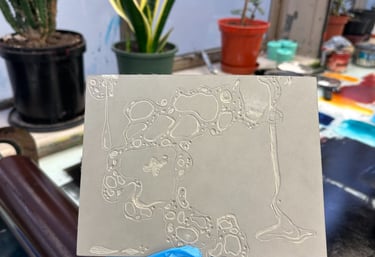

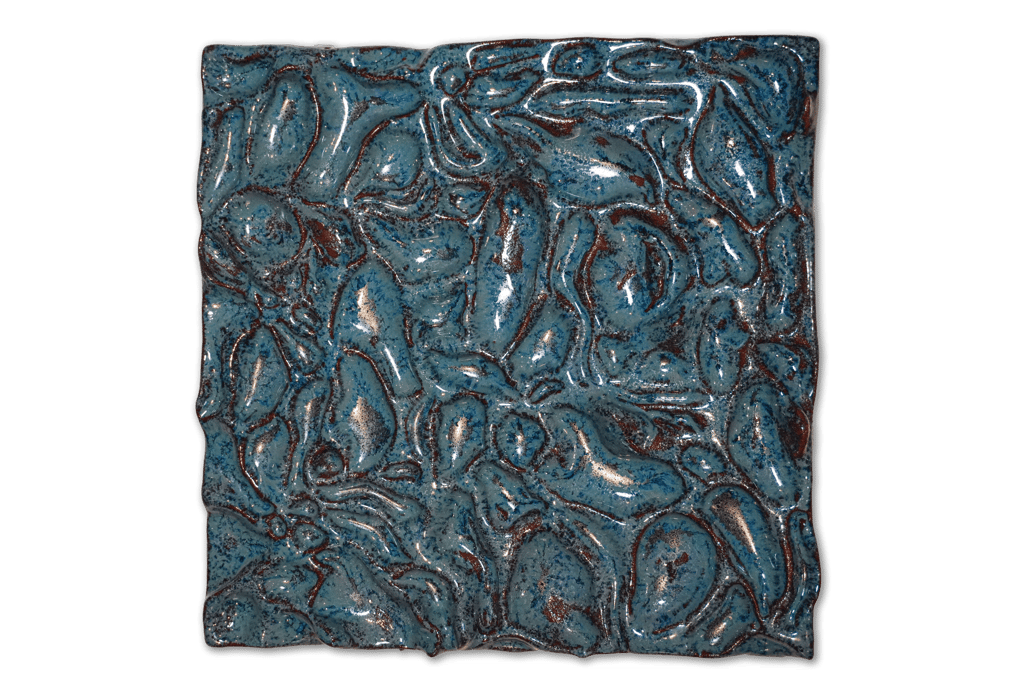

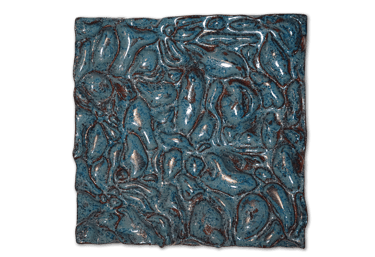

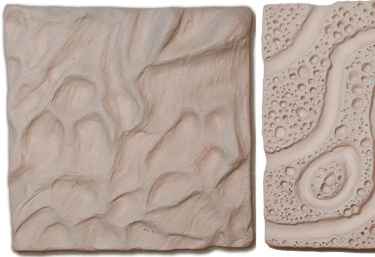

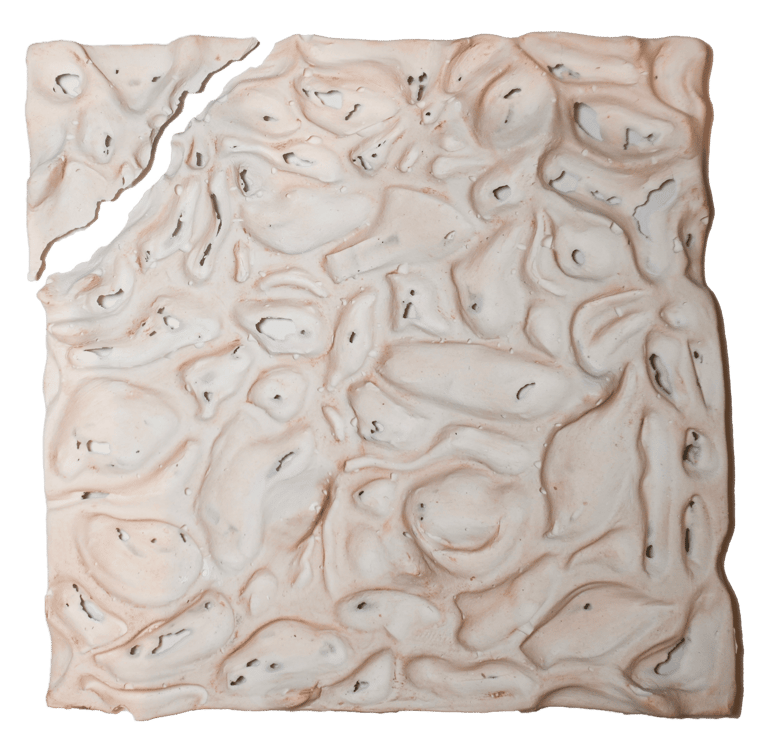

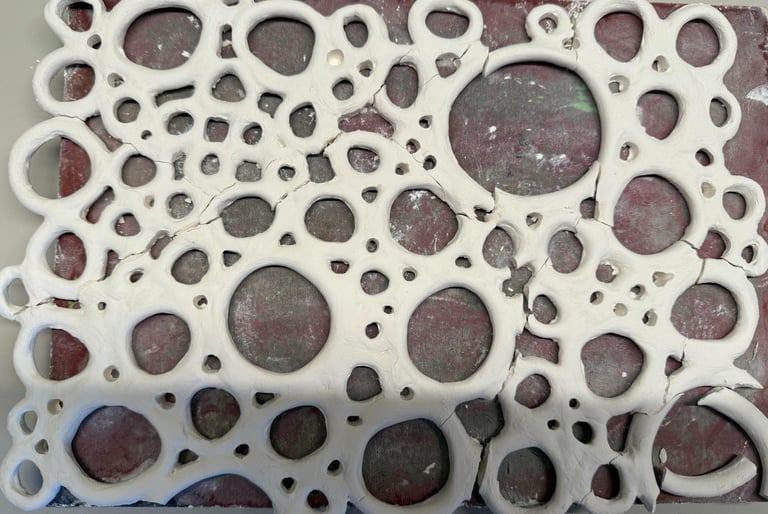

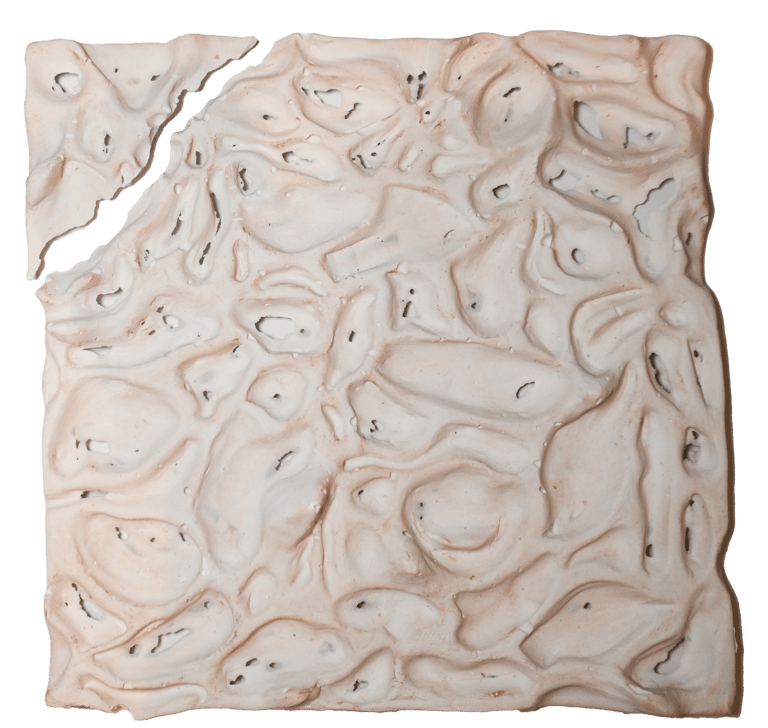

I sculpted low “puddle” volumes to see how a form behaves when it thins toward an edge. The geometry included hollows, undercuts and very thin areas so that drying and shrinkage would show. Before the first firing one form fractured; I repaired it and fired, but it opened again after glazing. Group crits read the break as information rather than failure and advised me to slow the drying around delicate zones and to keep the fragment as evidence. This was the beginning of my “brokenness” strand: keeping what happens, and using repair and loss as part of meaning (useful precedents here include material honesty in Eva Hesse’s early works and acceptance of accidental change as part of a piece, as in the reception of Duchamp’s cracked glass). From ripple drawings I carved shallow relief tiles that read as a sea floor after water has left. I compared unglazed stoneware with mid-dilution blue glaze. Unglazed plates let shadow and seam do most of the work; the glazed plates pooled light in the valleys and created a controlled cool tone. Crit feedback: keep both finishes, but use glaze sparingly so the field doesn’t tip into high contrast. The test confirmed that mid glaze + occasional unglazed plates allow rhythm without noise.

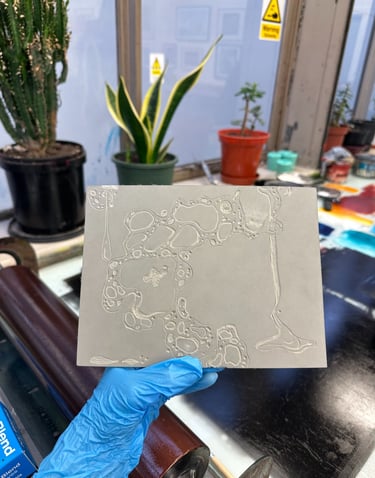

The next step was to silicone mould the clay relief as a matrix rather than as a surface to finish. Casting shifts the focus from one object to a system that can repeat, compare, and vary. This move is important for a practice about traces and remains. The mold is an index of contact. It holds the absence of the clay and allows the form to be read across different materials and states. In this frame, value sits in what is carried from one state to another rather than in a single perfect piece

Other tests

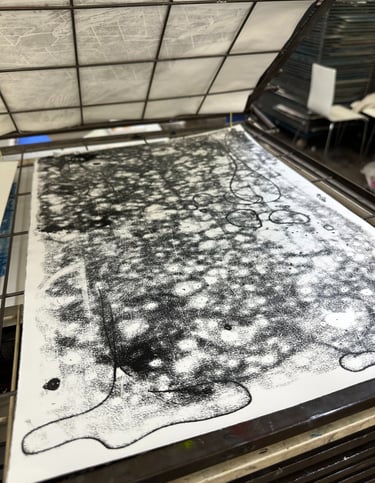

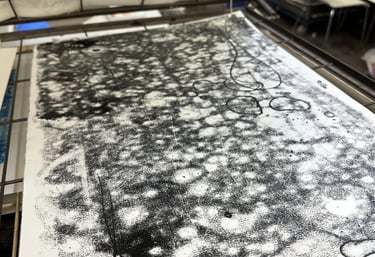

Polymer clay allowed quick curve studies but lacked the mineral edge I needed; these remained method sketches. Lino prints helped establish repeatable rhythm and spacing; the best lines translated back into carved relief directions. Both stayed as research tools rather than outcomes.

What I learned

1. Fracture and repair are part of the content. A fragment is a record, not a discard.

2. Unglazed + mid glaze in one field keeps depth without heavy contrast.

3. A slight translucent veil carries “hidden layers” better than full clarity.

4. Spacing and seam are not decoration; they are the compositional armature.

Next use

Fragments from the puddle series will continue to sit with relief fields; thin translucent elements will be used at a low tilt to register light; future plates will standardise clay bodies (grogged stoneware + selected light iron wash) to keep the field coherent.

Brokenness

I did not plan to work with broken things. The first porcelain ripple collapsed while drying and split into many parts. I asked myself: what if the break is the information I need? Where does energy concentrate? What does the edge record that a perfect surface hides? Keeping the fragments let me read thin zones, stress lines, and small pits as evidence of time, not as faults. The question changed from how do I avoid failure to how do I place what happened so it can be seen with clarity.

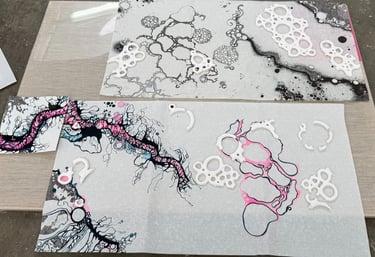

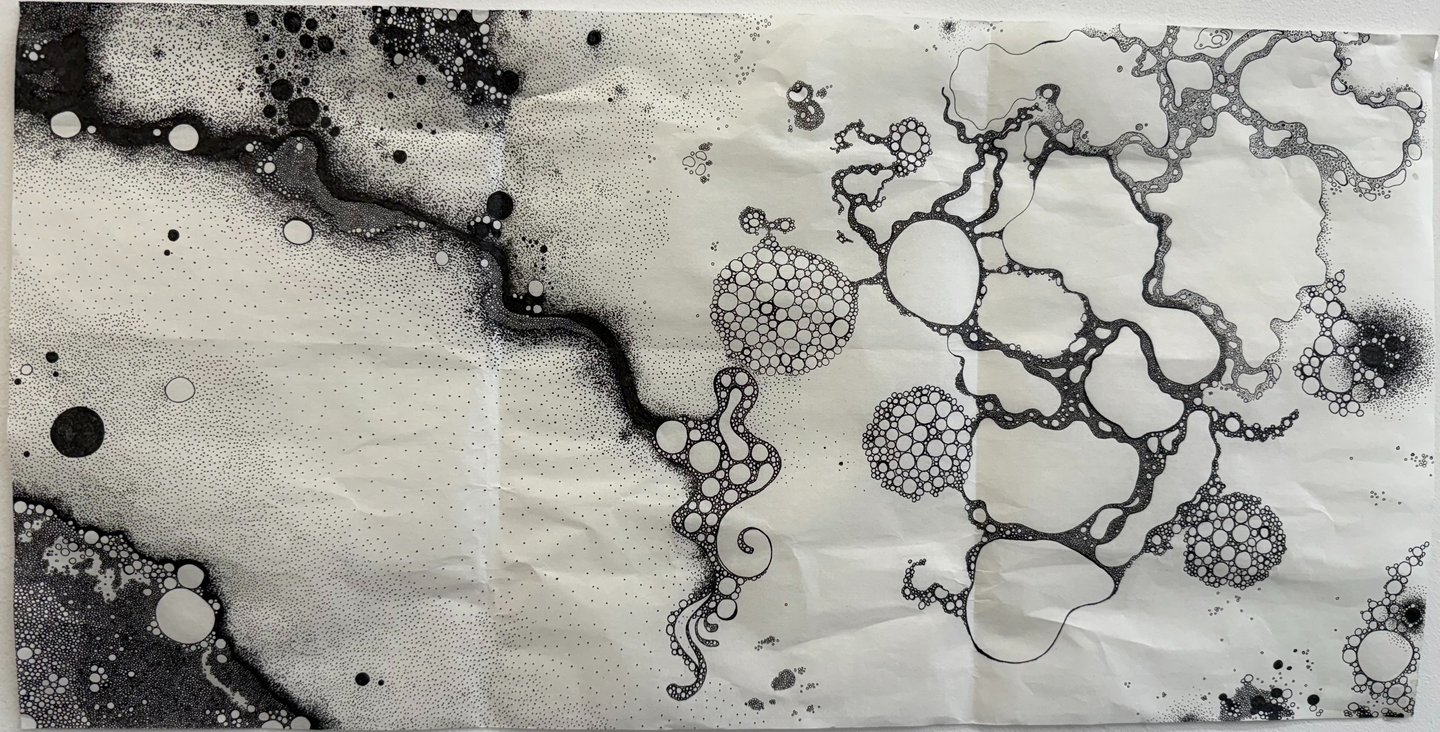

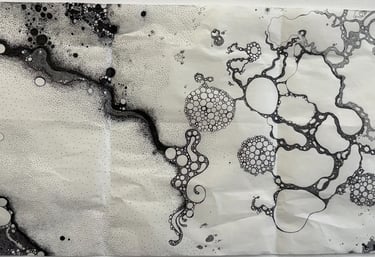

Connecting the Broken

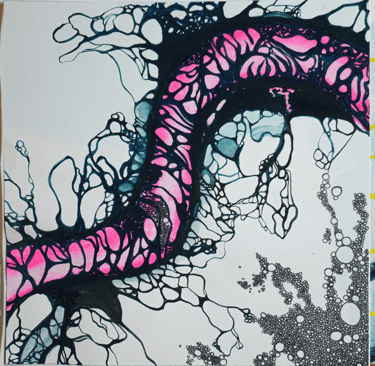

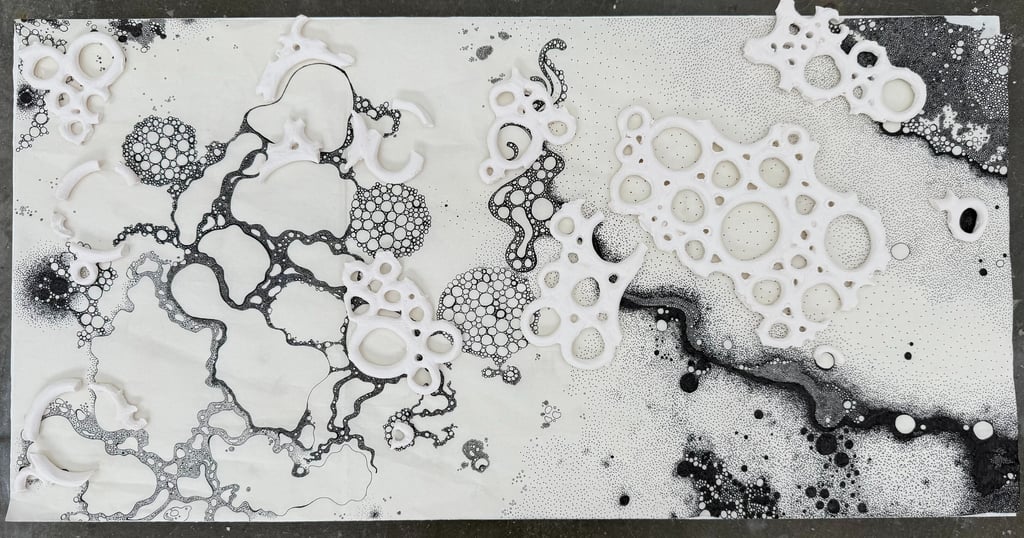

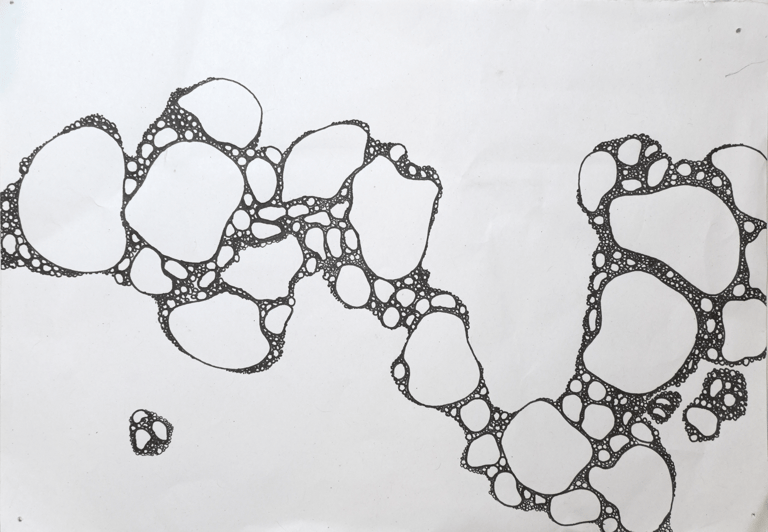

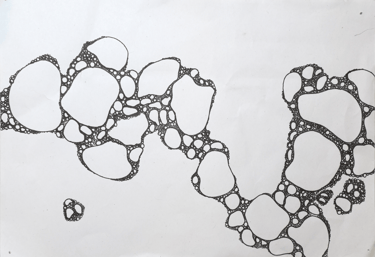

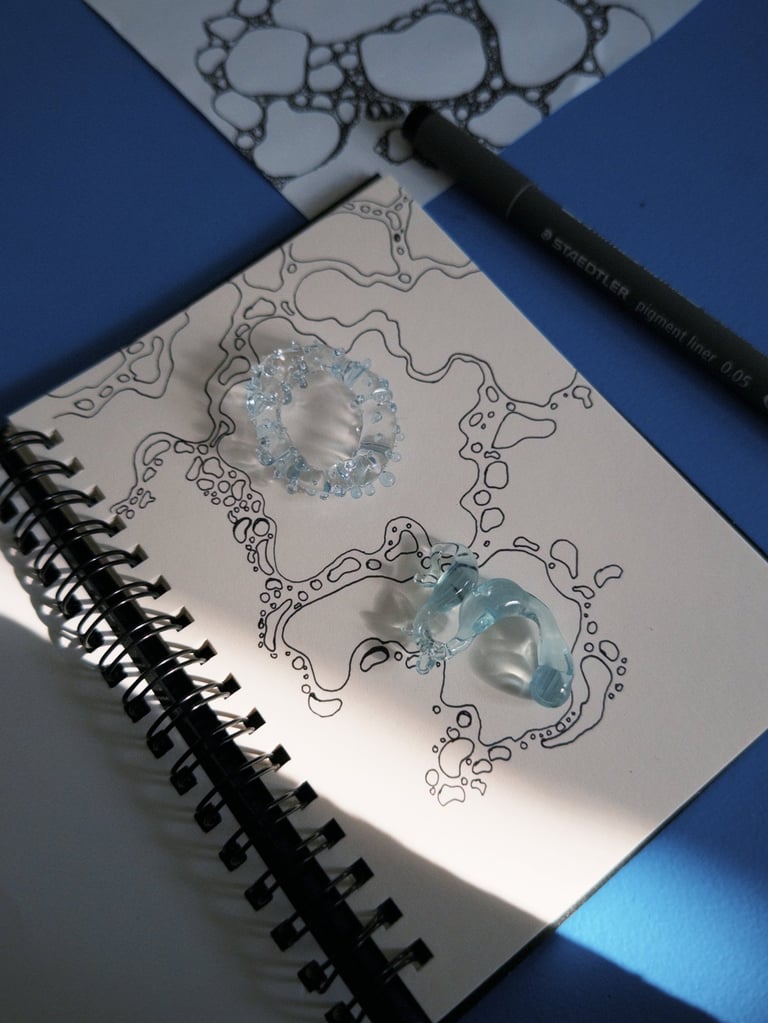

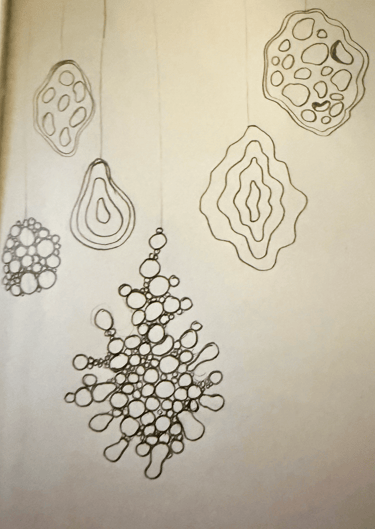

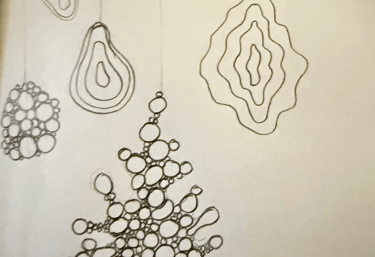

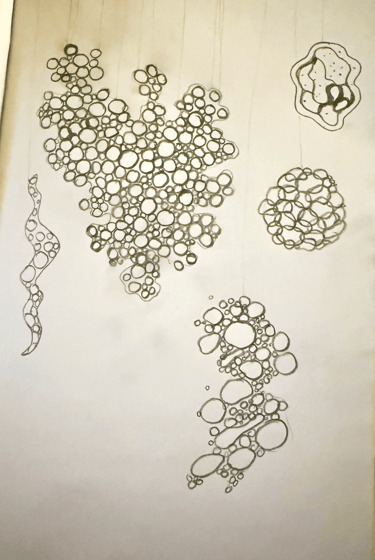

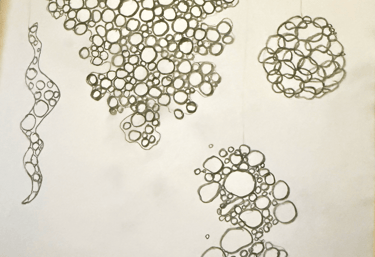

I began to draw the ripple as a way to keep time in a line. Bubble structures gave me a repeatable rhythm and a clear seam to follow. When the porcelain ripple split, I asked myself: can a drawing complete a fragment? Where does the break sit inside a field? I placed shards over the ripple drawings so the edge could meet the drawn seam. The fit was not literal, but the two parts recognised each other. A fragment is a contour made by force. The drawing is a contour made by attention. Together they read as one surface.

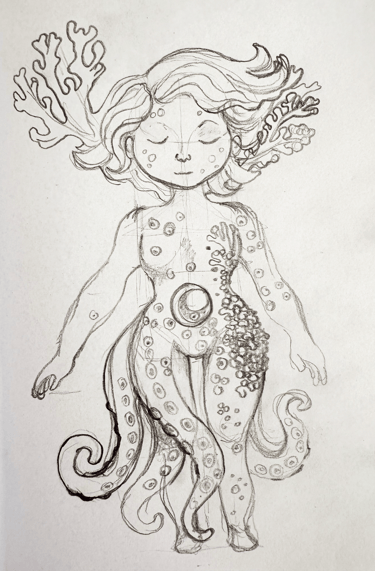

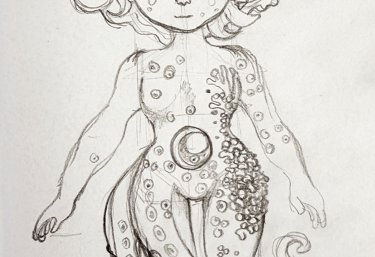

Sketches

The watery bodies began as a way to ask if a figure could be read through currents rather than outline. I was not aiming for anatomy. I wanted to see whether a body can appear from gaps, pools and seams that act like tide marks. These studies taught me that the work reads best when the body is implied by flow rather than drawn directly. This is why I did not move them into ceramic. The learning is kept and it informs spacing and aperture decisions in the installation.

series of ceramic puddle and ripple reliefs showing shifts in surface and form. The works include repaired cracks, unglazed plates and thinning clay edges that reveal texture, light and natural variation in the material.

Group critic with external tutor.

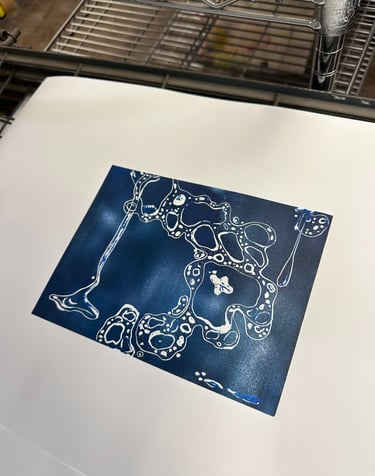

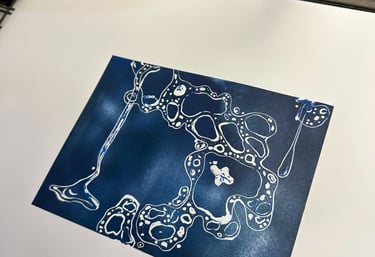

Silicone moulds and plaster casts taken from ripple shaped clay forms. The variations in pour depth create natural voids and uneven textures, capturing the traces of movement and the point where form begins to break away.

Plaster casts were used to study how height, edge and light read when the relief is repeated. A partial fill produced openings and thin bridges across the form. This outcome made negative space active. The interior that is usually solid becomes a field of small voids that admit light and air. The porous reading links to the wider concerns of the work: hidden layers, the record of time, and a language that accepts loss and repair. It also places the relief in a line of practices where casting is used to reveal what is usually unseen or left behind, for example the attention to absence in Rachel Whiteread, or the material evidence of process in Eva Hesse.

The mould and the casts therefore operate as tools for thinking. They test how a flow can be held as a trace, how residue can appear as structure, and how a field can remain open to air and light. The lesson taken forward is clear. Use the matrix to learn, keep porous results when they occur, and let negative space carry part of the content rather than filling it by habit.

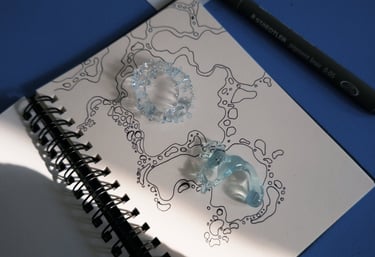

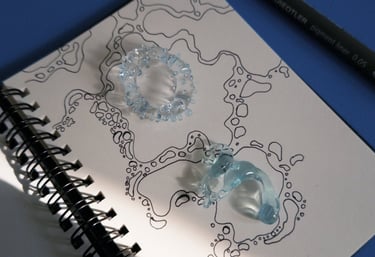

Material trials exploring ripple and puddle formations through polymer clay, glass, and print. The small prototype combines layered relief ideas in colour; glass fragments test translucency and reflection over drawn ripples; lino and monoprints extend these forms into two dimensional impressions.

From there I began shaping small ceramic growths that look like remains rather than specimens. They come from the same conditions that produced the breaks: thinning, pull, and points of collapse. I am not replicating coral or sea life. I am asking how a form continues after it fails. What can a fragment still do? How does a cluster hold light and air? Placed together, these parts read as a field that still carries motion.

This way of thinking sits inside a wider conversation. I look at practices that keep material truth active, for example early works by Eva Hesse where process and fragility are not cleaned away, and I note the acceptance of cracks as content in well known glass works that changed during transport. Archaeological display is also useful here, where shards are shown as knowledge rather than waste. These references help me argue that a fragment can carry the subject more directly than a polished whole.

In the MA show I placed a small set of broken growths on the sand so loss and repair could sit inside the environment of the work without becoming the headline. I learned to ask different questions during install: What gap lets the break read? Which surface gives the edge enough light? How can a clean plate support a shard without correcting it? Going forward I will keep pairing fragments with quieter plates and light can be read together. The aim is steady. Let breakage produce form and meaning, and place it so the viewer can see how the work learns.

Porcelain ripple fragments : A ripple form that collapsed while drying. I kept the shards to read thin zones and stress lines as information rather than faults.

MA show element exploded in firing : Post firing view of a layered ceramic work in multiple shards, showing fresh fracture surfaces and uneven thickness.

Small field of remains : A compact grouping that treats fragments as records rather than waste. The aim is to show continuity in form after failure without illustration of sea life.

The colour study with fine vein lines tested how a system of flow sits beneath a surface. I was thinking about life in water while avoiding illustration. The lines behave like currents and roots without naming coral. Later, on the beach at Rye, I saw strong ripple marks on wet sand. They confirmed that a field can hold a memory of movement after water leaves. I asked: is the work a picture, a map, or a residue. It can be all three if the placement is precise.

Ripple Drawing

Placing drawings with ceramic fragments makes the field read like a small geography. Edges touch and pull apart to form coasts and channels. This is not about declaring coral or continents. It is about how material and line carry the memory of flow. References that help me think about this include artists who let absence and trace do the work, such as Rachel Whiteread’s casting of spaces and Eva Hesse’s use of fragile continuity. I also take cues from archaeological displays where shards and diagrams sit together to produce knowledge. Mujeeb my tutor asked why glass or ceramic and not any other material like stone or plastic. The question was useful. Ceramic keeps a mineral record of air, heat and time that matches the subject, while thin resin or glass can manage light as a shallow layer. I remain open to site materials like sand and melted shaped glass when they help the reading, but the core decision is to use materials that hold trace without noise.

The outcome of this strand is a simple method. Draw a field of ripples, place fragments with measured gaps, and let the eye read motion and break together. What connects the pieces is not resemblance to sea life but a shared logic of flow, pause and memory.

Another group of drawings planned a hanging field of ripple rings. on paper the suspended circles held together as a light net. Once translated into clay the first ripple form failed at the thin joints, and the glass tests fractured when I connected more than three or four rings. This did not end the line of enquiry. It clarified a material decision. The idea of a suspended net remains useful, but the logic of my practice sits better on a ground where seam, shadow and residue are stable. The drawings stay as a record of that choice.

Bubble lattices and ripple maps continue to be my most direct tool. They set rhythm, show where gaps should sit, and let me place fragments with precision. When I put a shard on a drawn field the page reads like a small geography. I ask myself each time. Where does the break belong? what distance lets it speak without noise. The sketches make those answers visible.

what these sketches establish?

drawing is not decoration for the objects. It is where I test flow, seam and implication. Some ideas remain on paper by choice because the concept is carried there with more clarity than in a difficult object.